"To adjust how the line is plotted, check the documentation:"

...

...

@@ -87,7 +87,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "electric-purpose",

"id": "distinct-coordinate",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -96,7 +96,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "offshore-narrative",

"id": "green-dutch",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"As you can see there are a lot of options.\n",

...

...

@@ -109,7 +109,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "younger-recall",

"id": "adjacent-satellite",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -123,7 +123,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "fewer-wednesday",

"id": "external-meaning",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"Because these keywords are so common, you can actually set one or more of them by passing in a string as the third argument."

...

...

@@ -132,7 +132,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "romance-payment",

"id": "simple-korean",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -145,7 +145,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "democratic-setting",

"id": "pediatric-sullivan",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"<a class=\"anchor\" id=\"scatter\"></a>\n",

...

...

@@ -156,7 +156,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "homeless-opening",

"id": "bright-preparation",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -168,7 +168,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "sitting-scheme",

"id": "asian-mailing",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"The third argument is the variable determining the size, while the fourth argument is the variable setting the color.\n",

...

...

@@ -180,7 +180,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "trained-mechanism",

"id": "massive-relative",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -190,7 +190,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "convinced-framework",

"id": "positive-insight",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"where it also returns the number of elements in each bin, as `n`, and\n",

...

...

@@ -207,7 +207,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "convinced-cricket",

"id": "intensive-taste",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -222,7 +222,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "historical-content",

"id": "boolean-metropolitan",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"> If you want more advanced distribution plots beyond a simple histogram, have a look at the seaborn [gallery](https://seaborn.pydata.org/examples/index.html) for (too?) many options.\n",

...

...

@@ -236,7 +236,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "broken-deviation",

"id": "basic-cambridge",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -249,7 +249,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "shared-afghanistan",

"id": "twelve-assist",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"<a class=\"anchor\" id=\"shade\"></a>\n",

...

...

@@ -260,7 +260,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "changed-dressing",

"id": "stuck-teaching",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -270,7 +270,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "infrared-chinese",

"id": "metric-chemical",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"This can be nicely combined with a polar projection, to create 2D orientation distribution functions:"

...

...

@@ -279,7 +279,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "alternative-johnson",

"id": "democratic-israel",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -290,7 +290,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "primary-momentum",

"id": "connected-consideration",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"The area between two lines can be shaded using `fill_between`:"

...

...

@@ -299,7 +299,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "naughty-colors",

"id": "engaged-lottery",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -313,7 +313,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "acknowledged-illustration",

"id": "paperback-stylus",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"<a class=\"anchor\" id=\"image\"></a>\n",

...

...

@@ -324,7 +324,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "protected-toolbox",

"id": "acoustic-kitchen",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -340,7 +340,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "short-turkey",

"id": "frank-master",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"Note that matplotlib will use the **voxel data orientation**, and that\n",

...

...

@@ -352,7 +352,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "vulnerable-vegetation",

"id": "initial-passing",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -365,7 +365,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "danish-sandwich",

"id": "specialized-maintenance",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"> It is easier to produce informative brain images using nilearn or fsleyes\n",

...

...

@@ -377,7 +377,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "checked-helping",

"id": "weighted-publicity",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -390,7 +390,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "finished-canon",

"id": "manual-bacon",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"By default the locations of the arrows and text will be in data coordinates (i.e., whatever is on the axes),\n",

...

...

@@ -404,8 +404,10 @@

"In the examples above we simply added multiple lines/points/bars/images \n",

"(collectively called artists in matplotlib) to a single plot.\n",

"To prettify this plots, we first need to know what all the features are called:\n",

"Based on this plot let's figure out what our first command of `plt.plot([1, 2, 3], [1.3, 4.2, 3.1])`\n",

"\n",

"\n",

"\n",

"Using the terms in this plot let's see what our first command of `plt.plot([1, 2, 3], [1.3, 4.2, 3.1])`\n",

"actually does:\n",

"\n",

"1. First it creates a figure and makes this the active figure. Being the active figure means that any subsequent commands will affect figure. You can find the active figure at any point by calling `plt.gcf()`.\n",

...

...

@@ -423,7 +425,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "original-melissa",

"id": "earned-anaheim",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -434,7 +436,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "handy-anniversary",

"id": "valued-hungary",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"Note that here we explicitly create the figure and add a single sub-plot to the figure.\n",

...

...

@@ -451,7 +453,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "occupied-enforcement",

"id": "intensive-bruce",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -467,7 +469,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "encouraging-poultry",

"id": "upset-stanley",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"For such a simple example, this works fine. But for longer examples you would find yourself constantly looking back through the\n",

...

...

@@ -479,7 +481,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "elect-printer",

"id": "frank-treatment",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -492,7 +494,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "brief-auction",

"id": "occupational-astronomy",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"Here we use `plt.subplots`, which creates both a new figure for us and a grid of sub-plots. \n",

...

...

@@ -507,7 +509,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "binding-tobacco",

"id": "joint-chick",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -521,7 +523,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "canadian-africa",

"id": "illegal-spanish",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"Uncomment `fig.tight_layout` and see how it adjusts the spacings between the plots automatically to reduce the whitespace.\n",

...

...

@@ -532,7 +534,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "hollow-metadata",

"id": "accomplished-watershed",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -547,7 +549,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "willing-grade",

"id": "standing-course",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"<a class=\"anchor\" id=\"grid-spec\"></a>\n",

...

...

@@ -559,7 +561,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "loved-munich",

"id": "silent-voluntary",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -579,7 +581,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "invalid-roads",

"id": "roman-discharge",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"<a class=\"anchor\" id=\"styling\"></a>\n",

...

...

@@ -593,7 +595,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "roman-nicaragua",

"id": "english-yahoo",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -606,7 +608,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "appropriate-affairs",

"id": "constant-evolution",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"You can also set any of these properties by calling `Axes.set` directly:"

...

...

@@ -615,7 +617,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "afraid-fields",

"id": "suspended-biography",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -630,7 +632,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "hired-journey",

"id": "annual-hundred",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"> To match the matlab API and save some typing the equivalent commands in the procedural interface do not have the `set_` preset. So, they are `plt.xlabel`, `plt.ylabel`, `plt.title`. This is also true for many of the `set_` commands we will see below.\n",

...

...

@@ -641,7 +643,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "legislative-parallel",

"id": "trained-mouse",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -653,7 +655,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "possible-sacramento",

"id": "elementary-mentor",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"<a class=\"anchor\" id=\"axis\"></a>\n",

...

...

@@ -672,7 +674,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "executed-space",

"id": "capital-surgeon",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -693,7 +695,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "administrative-acquisition",

"id": "discrete-hartford",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"<a class=\"anchor\" id=\"faq\"></a>\n",

...

...

@@ -725,7 +727,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "directed-trouble",

"id": "fifty-relaxation",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -734,7 +736,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "indian-integrity",

"id": "fifty-sunglasses",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"> If you are using Jupyterlab (new version of the jupyter notebook) the `nbagg` backend will not work. Instead you will have to install `ipympl` and then use the `widgets` backend to get an interactive backend (this also works in the old notebooks).\n",

...

...

@@ -745,7 +747,7 @@

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"id": "pregnant-raising",

"id": "underlying-dealer",

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

...

...

@@ -755,7 +757,7 @@

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"id": "ceramic-liquid",

"id": "general-subscriber",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"Usually, the default backend will be fine, so you will not have to set it. \n",

...

...

%% Cell type:markdown id:ignored-think tags:

%% Cell type:markdown id:christian-smart tags:

# Matplotlib tutorial

The main plotting library in python is `matplotlib`.

It provides a simple interface to just explore the data,

while also having a lot of flexibility to create publication-worthy plots.

In fact, the vast majority of python-produced plots in papers will be either produced

directly using matplotlib or by one of the many plotting libraries built on top of

matplotlib (such as [seaborn](https://seaborn.pydata.org/) or [nilearn](https://nilearn.github.io/)).

Like everything in python, there is a lot of help available online (just google it or ask your local pythonista).

A particularly useful resource for matplotlib is the [gallery](https://matplotlib.org/gallery/index.html).

Here you can find a wide range of plots.

Just find one that looks like what you want to do and click on it to see (and copy) the code used to generate the plot.

> If you want more advanced distribution plots beyond a simple histogram, have a look at the seaborn [gallery](https://seaborn.pydata.org/examples/index.html) for (too?) many options.

<aclass="anchor"id="error"></a>

### Adding error bars

If your data is not completely perfect and has for some obscure reason some uncertainty associated with it,

plt.text(0.5,0.5,'middle of the plot',transform=plt.gca().transAxes,ha='center',va='center')

plt.annotate("line crossing",(1,-1),(0.8,-0.8),arrowprops={})# adds both text and arrow; need to set the arrowprops keyword for the arrow to be plotted

```

%% Cell type:markdown id:finished-canon tags:

%% Cell type:markdown id:manual-bacon tags:

By default the locations of the arrows and text will be in data coordinates (i.e., whatever is on the axes),

however you can change that. For example to find the middle of the plot in the last example we use

axes coordinates, which are always (0, 0) in the lower left and (1, 1) in the upper right.

See the matplotlib [transformations tutorial](https://matplotlib.org/stable/tutorials/advanced/transforms_tutorial.html)

for more detail.

<aclass="anchor"id="OO"></a>

## Using the object-oriented interface

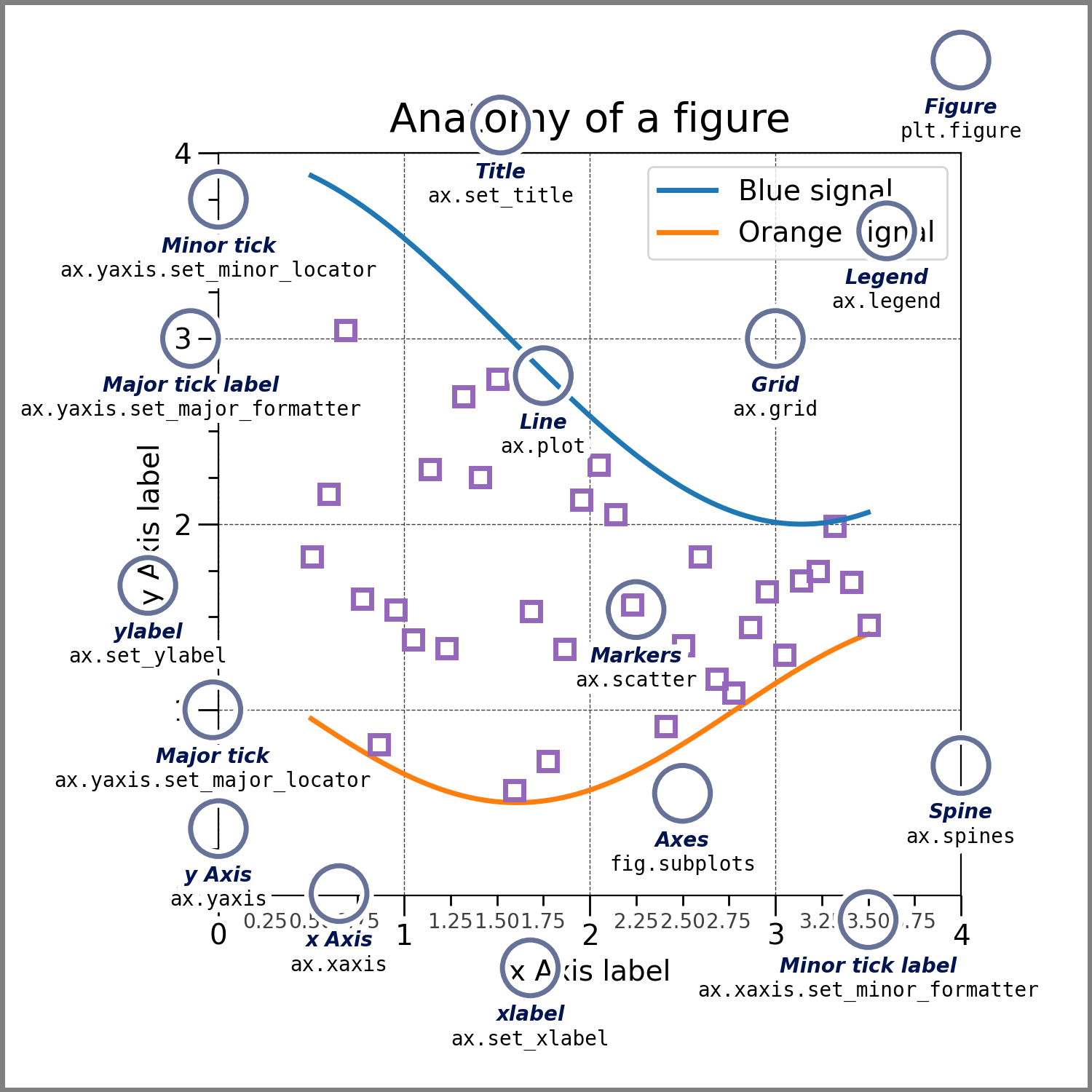

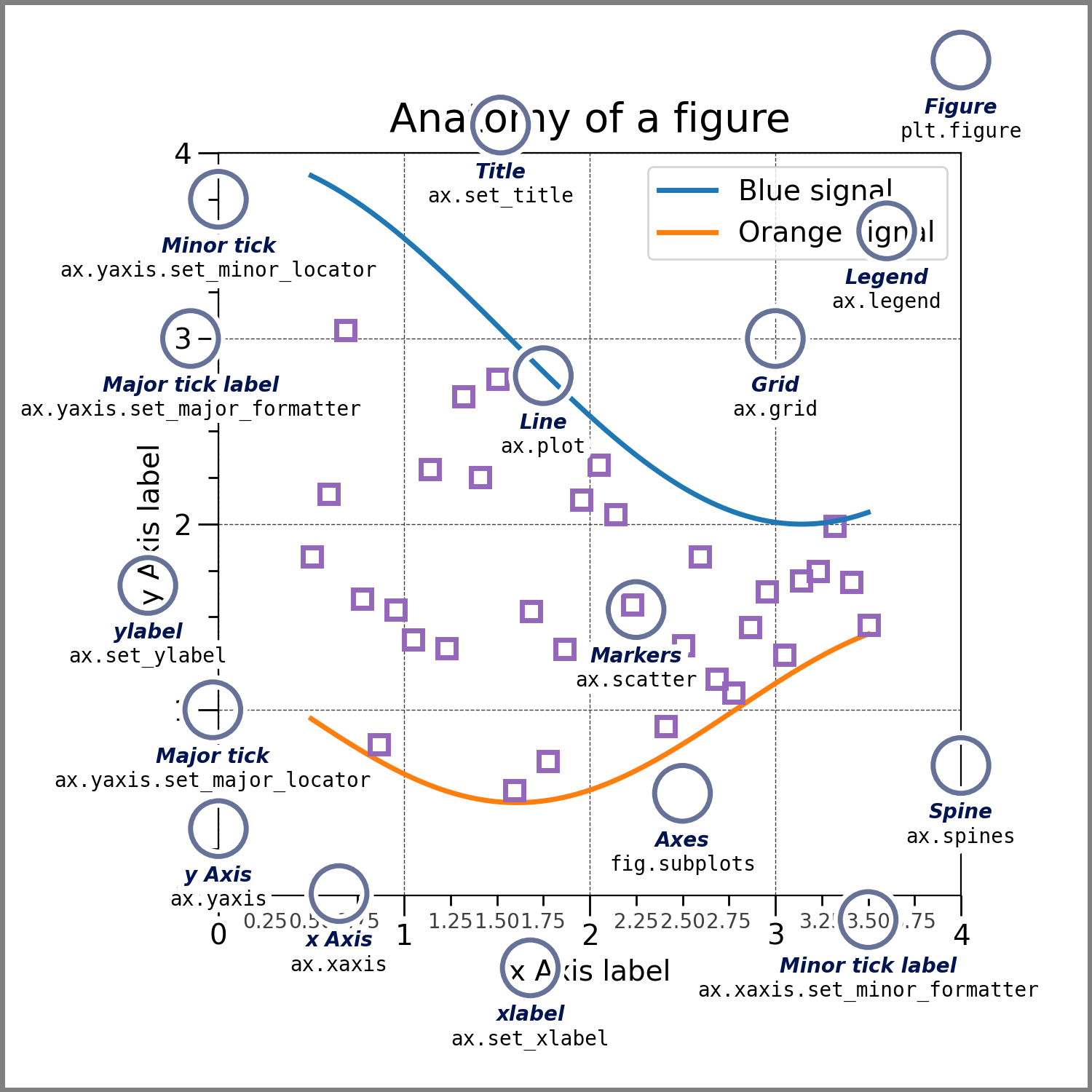

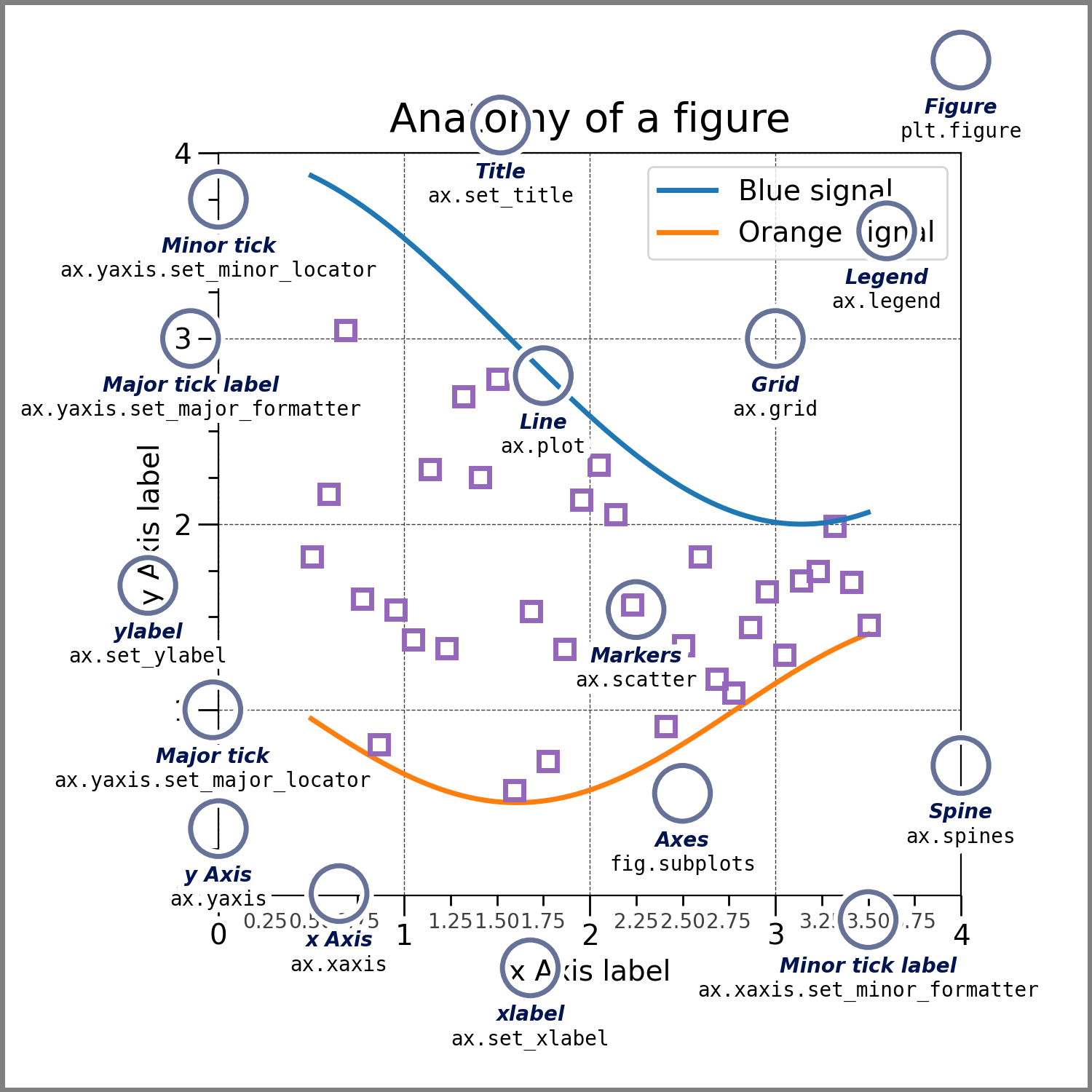

In the examples above we simply added multiple lines/points/bars/images

(collectively called artists in matplotlib) to a single plot.

To prettify this plots, we first need to know what all the features are called:

Based on this plot let's figure out what our first command of `plt.plot([1, 2, 3], [1.3, 4.2, 3.1])`

Using the terms in this plot let's see what our first command of `plt.plot([1, 2, 3], [1.3, 4.2, 3.1])`

actually does:

1. First it creates a figure and makes this the active figure. Being the active figure means that any subsequent commands will affect figure. You can find the active figure at any point by calling `plt.gcf()`.

2. Then it creates an Axes or Subplot in the figure and makes this the active axes. Any subsequent commands will reuse this active axes. You can find the active axes at any point by calling `plt.gca()`.

3. Finally it creates a Line2D artist containing the x-coordinates `[1, 2, 3]` and `[1.3, 4.2, 3.1]` ands adds this to the active axes.

4. At some later time, when actually creating the plot, matplotlib will also automatically determine for you a default range for the x-axis and y-axis and where the ticks should be.

This concept of an "active" figure and "active" axes can be very helpful with a single plot, it can quickly get very confusing when you have multiple sub-plots within a figure or even multiple figures.

In that case we want to be more explicit about what sub-plot we want to add the artist to.

We can do this by switching from the "procedural" interface used above to the "object-oriented" interface.

The commands are very similar, we just have to do a little more setup.

For example, the equivalent of `plt.plot([1, 2, 3], [1.3, 4.2, 3.1])` is:

%% Cell type:code id:original-melissa tags:

%% Cell type:code id:earned-anaheim tags:

``` python

fig=plt.figure()

ax=fig.add_subplot()

ax.plot([1,2,3],[1.3,4.2,3.1])

```

%% Cell type:markdown id:handy-anniversary tags:

%% Cell type:markdown id:valued-hungary tags:

Note that here we explicitly create the figure and add a single sub-plot to the figure.

We then call the `plot` function explicitly on this figure.

The "Axes" object has all of the same plotting command as we used above,

although the commands to adjust the properties of things like the title, x-axis, and y-axis are slighly different.

<aclass="anchor"id="subplots"></a>

## Multiple plots (i.e., subplots)

As stated one of the strengths of the object-oriented interface is that it is easier to work with multiple plots.

While we could do this in the procedural interface:

Here we use `plt.subplots`, which creates both a new figure for us and a grid of sub-plots.

The returned `axes` object is in this case a 2x2 array of `Axes` objects, to which we set the title using the normal numpy indexing.

> Seaborn is great for creating grids of closely related plots. Before you spent a lot of time implementing your own have a look if seaborn already has what you want on their [gallery](https://seaborn.pydata.org/examples/index.html)

<aclass="anchor"id="layout"></a>

### Adjusting plot layout

The default layout of sub-plots often leads to overlap between the labels/titles of the various subplots (as above) or to excessive amounts of whitespace in between. We can often fix this by just adding `fig.tight_layout` (or `plt.tight_layout`) after making the plot:

%% Cell type:code id:binding-tobacco tags:

%% Cell type:code id:joint-chick tags:

``` python

fig,axes=plt.subplots(nrows=2,ncols=2)

axes[0,0].set_title("Upper left")

axes[0,1].set_title("Upper right")

axes[1,0].set_title("Lower left")

axes[1,1].set_title("Lower right")

fig.tight_layout()

```

%% Cell type:markdown id:canadian-africa tags:

%% Cell type:markdown id:illegal-spanish tags:

Uncomment `fig.tight_layout` and see how it adjusts the spacings between the plots automatically to reduce the whitespace.

If you want more explicit control, you can use `fig.subplots_adjust` (or `plt.subplots_adjust` to do this for the active figure).

For example, we can remove any whitespace between the plots using:

You can also set any of these properties by calling `Axes.set` directly:

%% Cell type:code id:afraid-fields tags:

%% Cell type:code id:suspended-biography tags:

``` python

fig,axes=plt.subplots()

axes.plot([1,2,3],[2.3,4.1,0.8])

axes.set(

xlabel='xlabel',

ylabel='ylabel',

title='title',

)

```

%% Cell type:markdown id:hired-journey tags:

%% Cell type:markdown id:annual-hundred tags:

> To match the matlab API and save some typing the equivalent commands in the procedural interface do not have the `set_` preset. So, they are `plt.xlabel`, `plt.ylabel`, `plt.title`. This is also true for many of the `set_` commands we will see below.

You can edit the font of the text when setting the label:

Any figure you produce in the notebook will be shown by default once a cell successfully finishes (i.e., without error).

If the code in a notebook cell crashes after creating the figure, this figure will still be in memory.

It will be shown after another cell successfully finishes.

You can remove this additional plot simply by rerunning the cell, after which you should only see the plot produced by the cell in question.

<aclass="anchor"id="show"></a>

### I produced a plot in my python script, but it does not show up?

Add `plt.show()` to the end of your script (or save the figure to a file using `plt.savefig` or `fig.savefig`).

`plt.show` will show the image to you and will block the script to allow you to take in and adjust the figure before saving or discarding it.

<aclass="anchor"id="backends"></a>

### Changing where the image appears: backends

Matplotlib works across a wide range of environments: Linux, Mac OS, Windows, in the browser, and more.

The exact detail of how to show you your plot will be different across all of these environments.

This procedure used to translate your `Figure`/`Axes` objects into an actual visualisation is called the backend.

In this notebook we were using the `inline` backend, which is the default when running in a notebook.

While very robust, this backend has the disadvantage that it only produces static plots.

We could have had interactive plots if only we had changed backends to `nbagg`.

You can change backends in the IPython terminal/notebook using:

%% Cell type:code id:directed-trouble tags:

%% Cell type:code id:fifty-relaxation tags:

``` python

%matplotlibnbagg

```

%% Cell type:markdown id:indian-integrity tags:

%% Cell type:markdown id:fifty-sunglasses tags:

> If you are using Jupyterlab (new version of the jupyter notebook) the `nbagg` backend will not work. Instead you will have to install `ipympl` and then use the `widgets` backend to get an interactive backend (this also works in the old notebooks).

In python scripts, this will give you a syntax error and you should instead use:

%% Cell type:code id:pregnant-raising tags:

%% Cell type:code id:underlying-dealer tags:

``` python

importmatplotlib

matplotlib.use("osx")

```

%% Cell type:markdown id:ceramic-liquid tags:

%% Cell type:markdown id:general-subscriber tags:

Usually, the default backend will be fine, so you will not have to set it.

Note that setting it explicitly will make your script less portable.

Based on this plot let's figure out what our first command of `plt.plot([1, 2, 3], [1.3, 4.2, 3.1])`

Using the terms in this plot let's see what our first command of `plt.plot([1, 2, 3], [1.3, 4.2, 3.1])`

actually does:

1. First it creates a figure and makes this the active figure. Being the active figure means that any subsequent commands will affect figure. You can find the active figure at any point by calling `plt.gcf()`.